Stress fracture: symptoms, treatment and prevention

Unlike a conventional fracture, it is not caused by a sudden impact but by excessive mechanical stress on the bone, often related to sport or certain repetitive activities. This means that the bones are subjected to repeated stress at a rate that exceeds their capacity for remodelling.

In athletes, the tibia and foot are among the most affected areas, as they are both heavily used during running and jumping.

What are the symptoms of a stress fracture?

The symptoms appear gradually. The pain is initially localised , then becomes more pronounced during exercise and subsides at rest. The following are often observed:

- localised pain that increases when walking or running;

- tenderness when the affected bone is touched;

- sometimes swelling or oedema;

- functional limitation with difficulty putting weight on the foot or running.

These clinical signs are characteristic of stress fractures, regardless of their location.

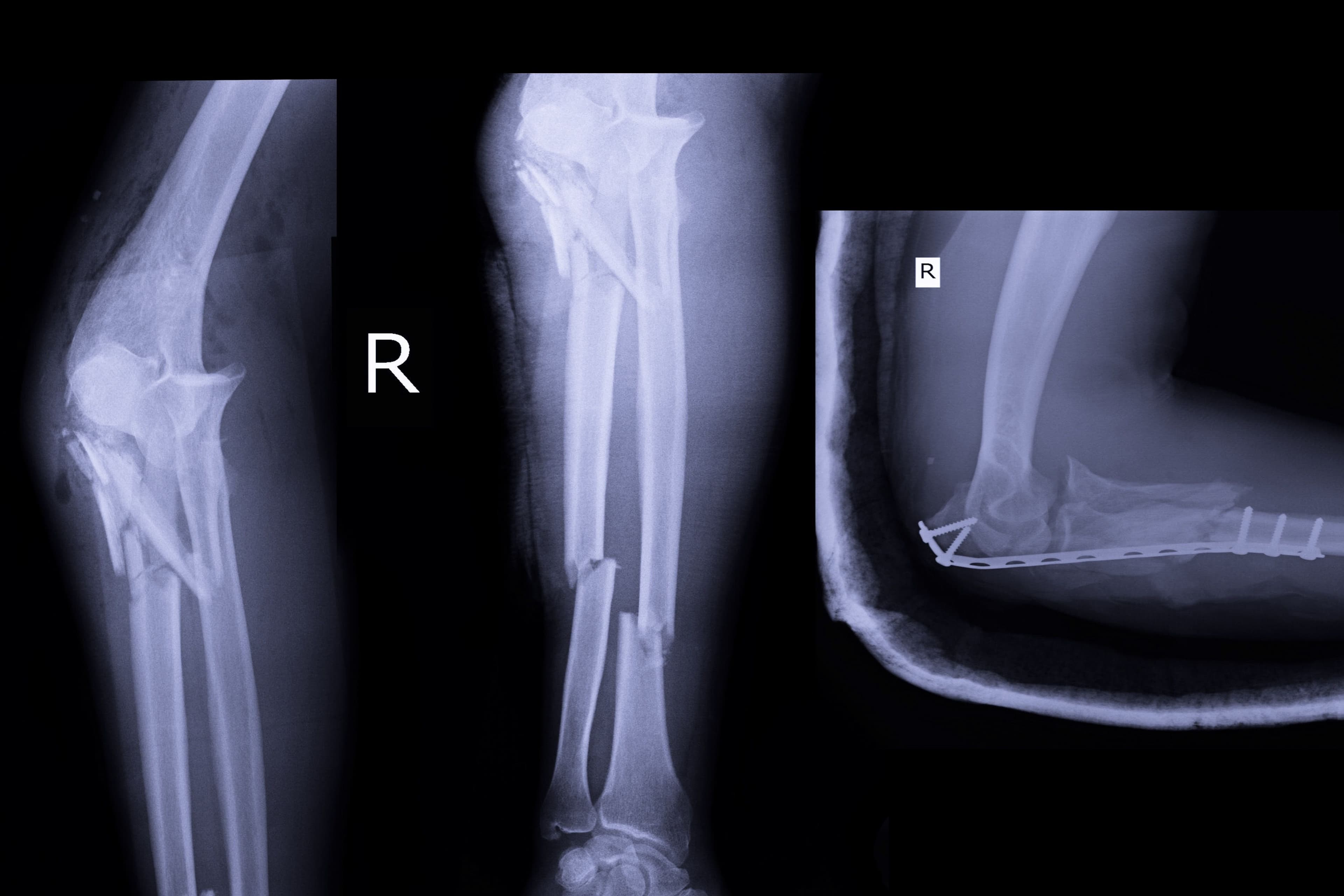

Imaging is essential for diagnosis. However, standard X-rays are not sensitive and often come back negative (70%) in the early stages, and are almost always negative during "stress reactions". On the other hand, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is the gold standard test for diagnosing this type of injury.

What are the risk factors for a stress fracture?

There are various factors involved in stress fractures. These can be classified as follows.

Intrinsic factors: female gender, steroid use, and nutritional deficiencies in calcium and vitamin D.

Extrinsic factors: intense or high-volume physical activity. A sudden increase in the volume or intensity of exercise. Individual biomechanical factors ( ). Changes in footwear. Environmental factors such as running on hard surfaces.

It is usually a combination of these factors that causes stress fractures.

How can stress fractures be prevented?

To prevent stress fractures, it is essential to adopt a few good habits in your daily life.

A balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D promotes bone strength.

Choosing the right equipment, especially well-fitting walking or running shoes that provide good support, also plays an important role.

To limit stress on the skeleton, it may be helpful to incorporate less demanding activities, such as cycling or swimming.

When starting a new activity, it is best to progress in stages, increasing the training load gradually, for example by 10% per week.

Finally, regular muscle training helps to preserve bone density, especially as we age, and thus helps to reduce the risk of stress fractures.

How can a stress fracture be healed?

Healing involves several essential steps:

- Rest from sports: stop activities that cause pain (running, jumping).

- Reduced weight-bearing: If a stress fracture is suspected in a high-risk area, immediate weight-bearing relief using crutches is recommended until the diagnosis is confirmed. The average healing time is between 6 and 12 weeks, depending on the location and severity of the fracture.

- Wearing a foot orthosis to reduce stress on the affected limb.

- Gradual rehabilitation: maintaining muscle strength, correcting sporting movements, supervised resumption of activity.

- In the case of a femoral neck fracture, the consequences of displacement are significant and warrant surgical treatment.

Stress fractures of the foot and tibia

Stress fractures are common in the metatarsals and tibia. These areas are subject to high mechanical stress, particularly in athletes who participate in running, basketball, dancing or football.

Can you walk with a stress fracture?

It is sometimes still possible to walk, especially at the beginning, because the bone is not completely broken. However, continuing to put weight on the area can aggravate the injury and prolong healing. Painful walking or persistent discomfort should therefore be cause for concern and lead to a medical consultation.

Robinson, P. G., Campbell, V. B., Murray, A. D., Nicol, A., & Robson, J. (2019). Stress fractures: diagnosis and management in the primary care setting. British Journal of General Practice, 69(681), 209–300. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19x702137

Credits : Shutterstock - Pepermpron