The spinal column: definition and role

When we talk about back pain, we often refer to the spinal column, or ‘rachis’ by its scientific name. How is it structured? How does it work? Here are the answers.

What is the spinal column?

The spinal column, also known as the ‘rachis’, is made up of 33 stacked vertebrae held together by numerous muscles and ligaments. Between each vertebra are intervertebral discs, which play an essential shock-absorbing role.

From top to bottom there are :

- 7 cervical vertebrae in the neck;

- 12 thoracic vertebrae in the middle of the back;

- 5 lumbar vertebrae in the lower back;

- 5 sacral vertebrae forming the sacrum at buttock level;

- 3 to 5 vertebrae forming the coccyx in the crease of the buttocks.

The spinal column supports the entire human skeleton, protects the spinal cord and allows the body to move(1).

The spinal column: 7 cervical vertebrae and 12 dorsal vertebrae

The cervical spine is made up of 7 vertebrae located in the upper back, at the level of the neck. The first vertebra, which directly supports the weight of the skull, is called the ‘atlas’, in reference to the mythological god who carries the weight of the earth on his shoulders. The second is the ‘axis’, which is involved in head movement by allowing the atlas to pivot above it(3).

The other 5 cervical vertebrae are designated by their numbers. The body of each vertebra supports the weights of those above and the skull, while another part, the ‘arch’, forms a channel along the spine to house and protect the spinal cord.

Below the cervical vertebrae are the twelve dorsal vertebrae, also known as the ‘thoracic spine’. These much larger vertebrae are located in the middle of the back and fulfil much the same role as the cervical vertebrae (rotation of the upper vertebra, protection of the spinal cord)(3).

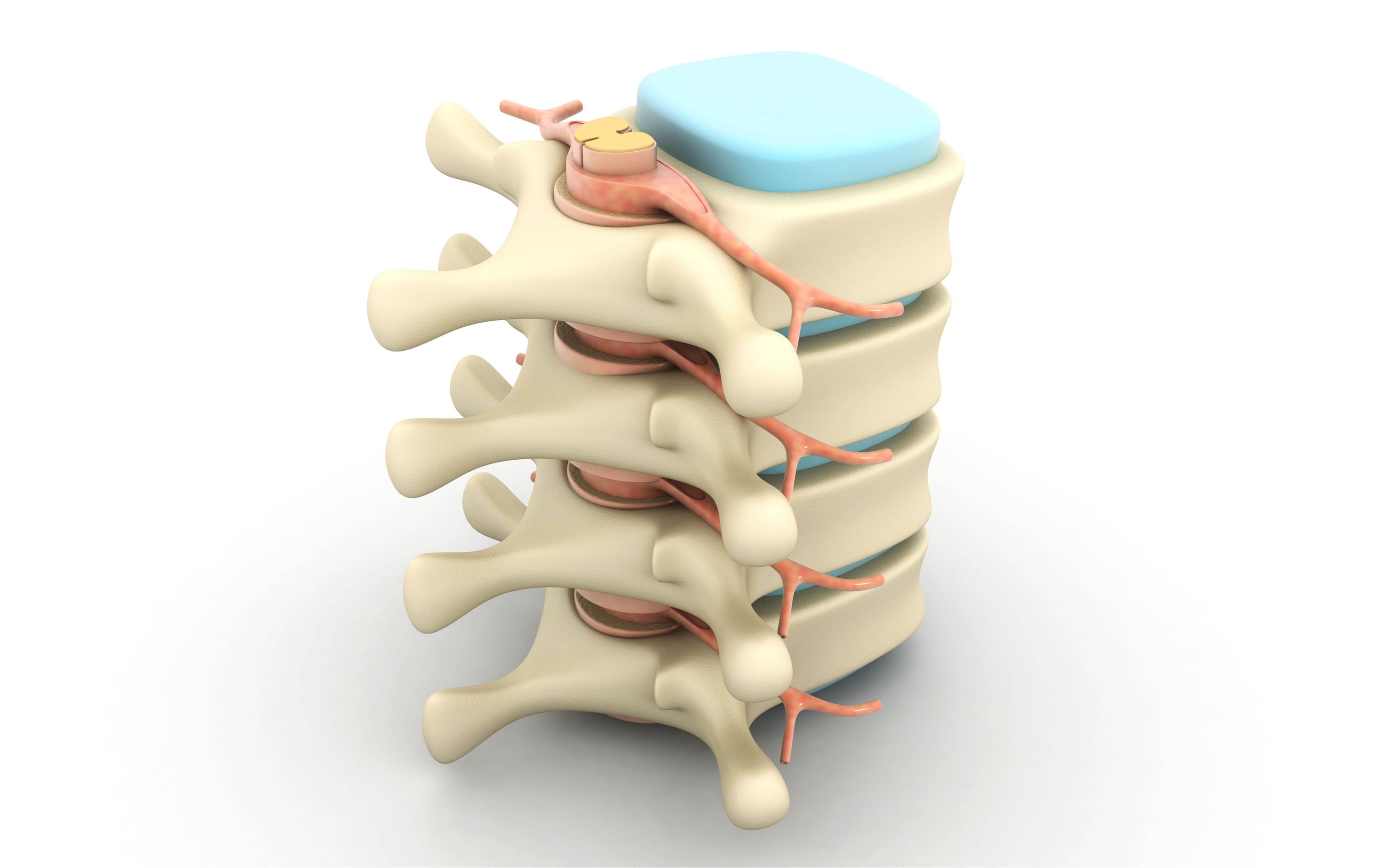

3D modelling of the spinal column

The 5 vertebrae of the lower back, the sacrum and the coccyx

The 5 ‘lumbar’ vertebrae are located below the dorsal vertebrae. Their bodies are much larger than those of the dorsal and cervical vertebrae. They form the lumbar spine and lie above the sacrum.

The sacrum, also known as the ‘sacral spine’, is made up of the 5 ‘sacral’ vertebrae, which are fused together in adulthood to form a bony block. It lies above the coccyx(3).

The coccyx is a bony vestige, formerly the tail of mammals(4). In principle, it is made up of 4 coccygeal vertebrae fused together, and supports the abdominal organs. The name of this small triangular bone comes from the Greek ‘kokkus’, meaning cuckoo, by analogy with the shape of the bird's beak.

Intervertebral discs with a protective role

The vertebrae are bony bodies made up of a cylinder, which bears the brunt of the effort. Between them are discs of cartilage. These serve to protect the spinal column from trauma. Each of these discs has an inner core, called the ‘nucleus pulposus’, and an outer ring, called the ‘annulus fibrosus’(1).

The vertebrae and discs are joints that ensure the mobility of the spinal column. The vertebrae are joined and articulated together by 3 joints : a disc placed between the vertebral bodies and 2 other small symmetrical posterior joints that join the posterior part of the vertebrae further back. These two protruding elements are called ‘apophyses’. They form a joint with the apophyses of the upper and lower vertebrae, limiting the movement of the cylinders and ensuring the cohesion of the spinal column.

Sometimes, the spinal column is subjected to severe stress: carrying heavy objects, intense sporting effort, twisting the back, etc. The discs can then ‘slip’, fracture or dislocate. If the nucleus pulposus protrudes from the disc, the result is a herniated disc(2)!

When you suffer from lumbar osteoarthritis, it is these same discs that are affected. The pathology results in their progressive wear and tear in the lumbar and dorsal vertebrae(5).

- Anatomie de la colonne vertébrale. Groupe hospitalier de la Rochelle-Ré-Aunis.

- Fiche anatomie : Rachis, Colonne vertébrale. Société Française de Rhumatologie.

- Raven PH, Mason KA, Johnson GB , Losos JB, Singer SR. Biologie, De Boeck Superieur, 2017, page 699.

- Ferembach D, Susanne C, Chamla MC. L'Homme, son évolution, sa diversité : manuel d'anthropologie physique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1986, page 97.

- Pathologies rachidiennes. Centre du rachis (en ligne).