Fracture: definition, causes and treatment

What is a fracture?

A fracture is a partial or total break in a bone, caused by direct trauma (such as an accident or fall) or by a pathology that weakens the bone, such as osteoporosis(1). Fractures are common traumatic injuries that affect the integrity of the bone structure. When a fracture heals, the body sets in motion a natural process of bone repair and regeneration, generally restoring the damaged skeletal organ to its previous state. However, around 10% of fractures do not heal properly without medical treatment. Various treatments include analgesia, immobilisation and surgery to reduce bone fractures and promote optimal consolidation(2).

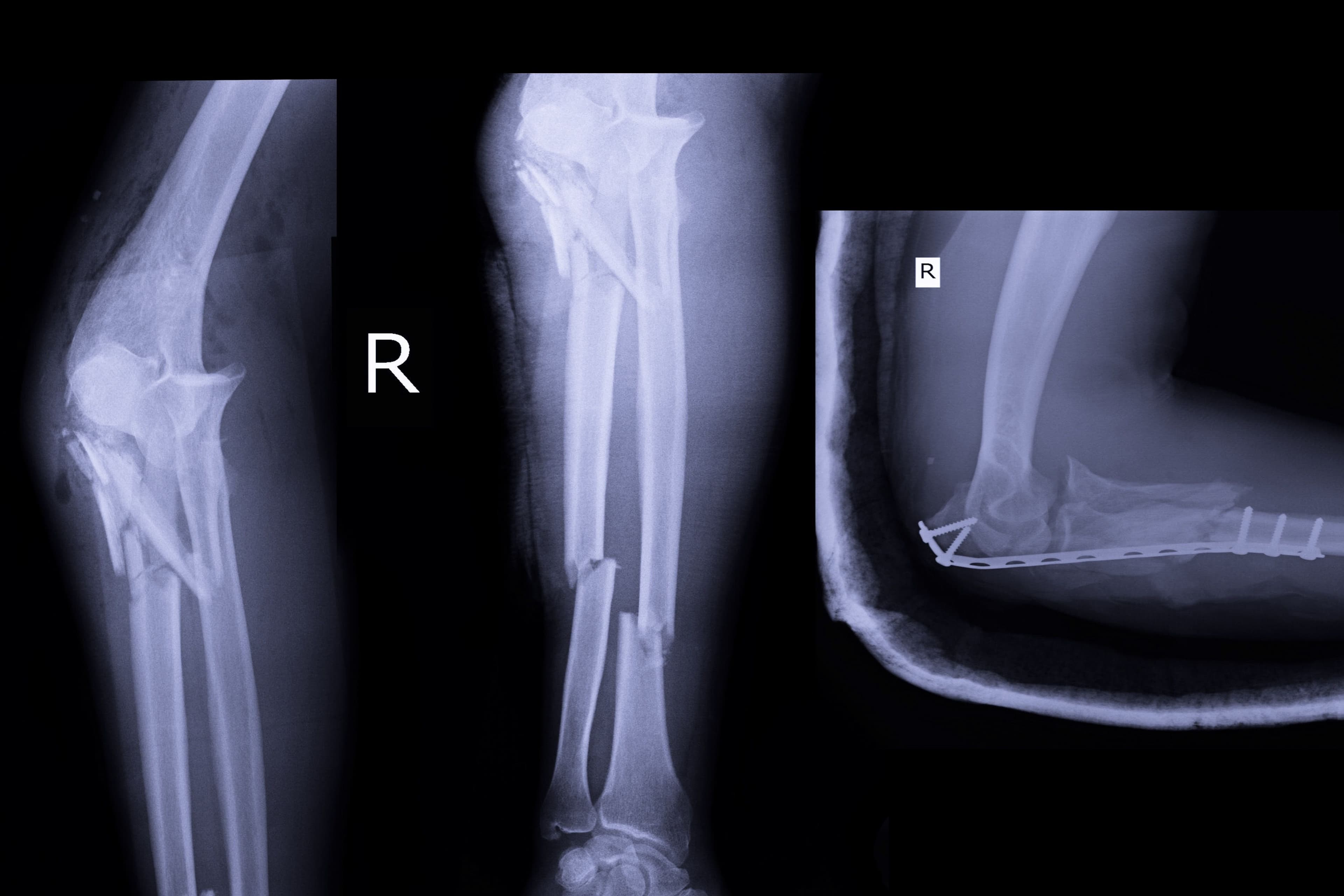

What are the different types of fracture?

Traumatic fracture

This is a bone fracture caused by injury or direct impact, often as a result of an accident or fall. These fractures may be with or without displacement (the broken pieces of bone remain normally aligned) (3).

Pathological fracture

This occurs when the bone is weakened by an underlying disease, such as osteoporosis, infection or bone cancer, making it more susceptible to fracture even after minor trauma (3).

Stress fracture

This is the result of repeated pressure or strain on a bone, as often occurs in athletes, especially during certain activities, such as jumping, walking with a heavy bag or running. These fractures generally occur in weight-bearing bones, such as those in the foot or lower leg. And because they occur gradually, they are often difficult to diagnose (4).

Open fracture (compound fracture)

This type of fracture, which involves a break in the skin and soft tissue, exposing the bone, is usually caused by significant trauma. This increases the risk of infection and often requires immediate surgical intervention (5).

Closed fracture

Unlike open fractures, a closed fracture involves a break in the bone without breaking the skin. This type of fracture can be caused not only by trauma, but also by underlying pathology. Although generally less serious than an open fracture, a closed fracture nevertheless requires appropriate treatment to ensure proper healing (6).

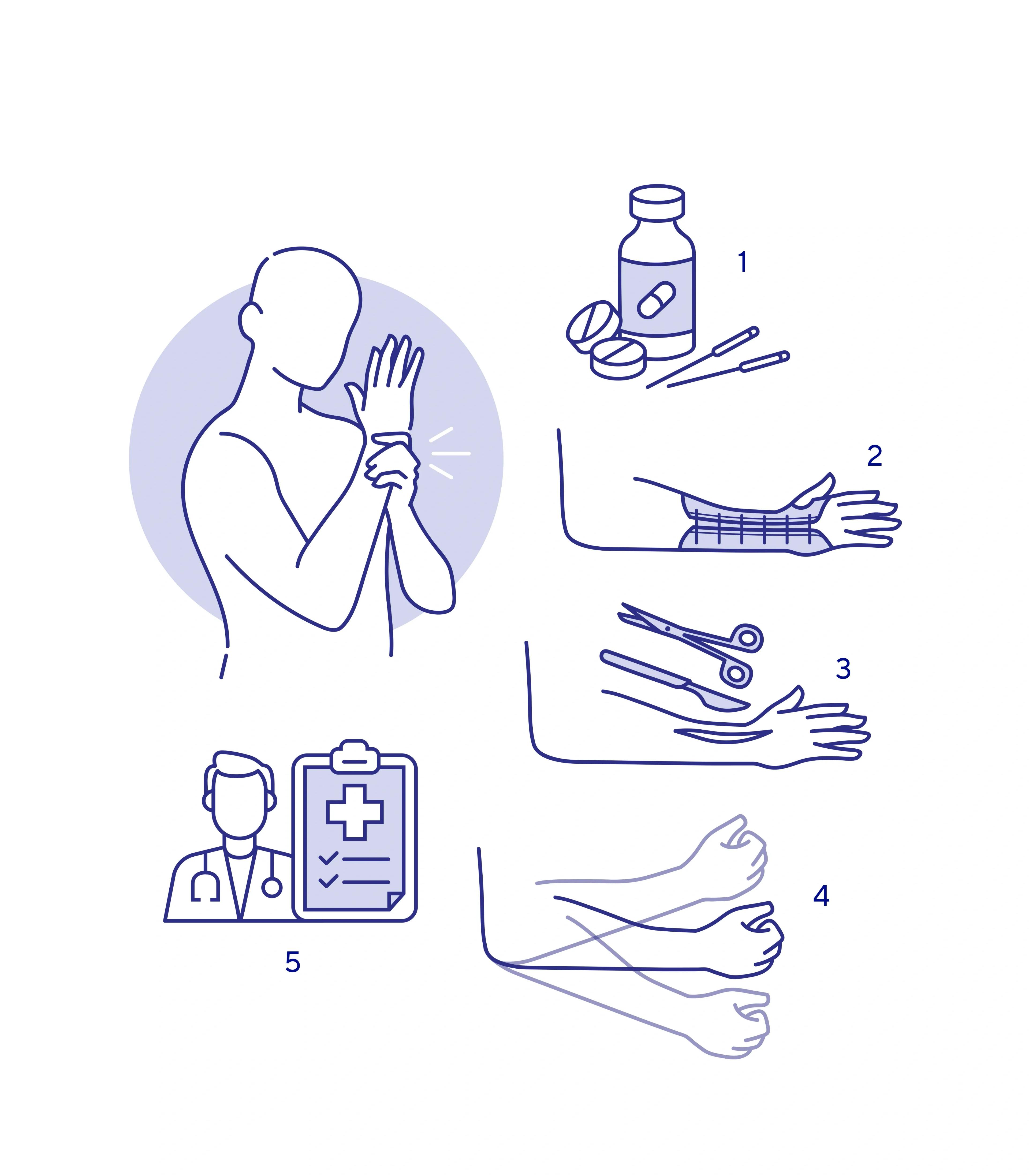

How is a fracture treated and relieved?

There are several approaches to treating and alleviating a fracture, depending on its severity, type and location. Here are the main methods, based on recent research:

- Pain management: Pain control is essential when managing fractures. Pain-relieving drugs prescribed by the doctor and acupuncture, in which needles are inserted at the precise points of pain, are therapies used to relieve pain(7).

- Immobilisation: The first step is generally to immobilise the fracture. This can be done with a splint (usually worn for three to five weeks), a cast (usually worn for six to eight weeks) or traction. These methods ensure that the fracture heals properly by holding the bone fragments in place during healing. Thuasne offers a wide range of solutions for immobilising the affected limb.

- Surgery: In the case of a complex fracture, surgery may be necessary to achieve optimal healing. There are several options available to the surgeon: open reduction and internal fixation, which involves putting the bone fragments back into place and fixing them with metal hardware; external fixation, which uses pins or screws inserted into the bone for external stabilisation; intramedullary nailing, which reinforces the bone from the inside with a metal rod; and finally, bone grafting, used to replace the missing bone with natural or synthetic bone tissue. The choice of technique depends on many factors, such as the type of fracture, the patient's age and physical condition.

- Rehabilitation: After immobilisation or surgery, rehabilitation is often necessary to restore full mobility and strength to the fractured area. This may include specific exercises and physiotherapy sessions.

- Medical follow-up: Regular consultations with an orthopaedic surgeon are essential to monitor the healing of the fracture and adjust treatment if necessary.

In summary, fracture treatment combines pain relief, immobilisation, rehabilitation and, if necessary, surgery to promote bone healing.

Are there any predispositions to fracture?

Athletes

Contact sports (football, basketball, hockey, etc.) are particularly exposed to repeated shocks and sudden movements, thus increasing the risk of fractures.

Stress fractures

Fatigue fractures, resulting from repeated microtrauma, are a common problem among athletes. Women are at increased risk, particularly those with menstrual disorders, low body mass or low energy intake. These factors, sometimes combined with low bone mass, increase vulnerability to this type of fracture(10).

The elderly

The age-related decrease in bone density, particularly pronounced after the age of 50, makes people more vulnerable to fractures. This bone fragility, characteristic of osteoporosis, considerably increases the risk of fractures(14).

Women

The menopause accelerates bone loss in women due to the reduction in oestrogen, significantly increasing the risk of fractures(14).

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is associated with an increased risk of hip and proximal humeral fracture. In these patients, bone quality is often compromised, which is linked to the accumulation of advanced glycation products within the bone tissue, favouring the development of fractures(9).

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis, a metabolic disease characterised by a reduction in mineral density and bone strength, is the main cause of fragility fractures in the elderly. Low bone density significantly increases the risk of fractures, particularly of the hips and wrists(8).

FAQ about fracture

Our medical team answers the questions you may have.

The healing process for a fracture generally takes between 3 and 12 weeks, depending on various factors such as the location of the fracture, the patient's age and the severity of the injury. In general, a simple fracture heals more quickly than a complex or open fracture, and younger patients often recover more quickly than older patients(11).

A broken bone and a fracture are actually synonymous terms used to describe the same condition: the breakdown of bone continuity. However, perceptions vary between these two terms, particularly among patients. One study showed that although healthcare professionals use the terms ‘fracture’ and ‘broken’ interchangeably, patients often perceive a difference in severity. In the study, only 45% of respondents understood the terms fractured and broken to be synonymous. However, 55.7% of respondents described a fracture as less severe than a broken bone, while 62.1% perceived a broken bone as more severe(12).

In summary, from a medical point of view, there is no difference between a broken bone and a fracture, but perceptions often vary between these two terms, with the word ‘broken’ often being perceived as more serious by patients.

Immobilisation maintains and stabilises the bone fragments in the correct position, thereby facilitating the formation of the bone callus required for healing. This prevents the fragments from moving during the bone consolidation process, which will limit damage to the soft tissues (muscles, nerves, blood vessels). In addition, by limiting the movement of the fractured bone, immobilisation helps to reduce pain by preventing the bone fragments from rubbing or moving(13).

- Johnston CB, Dagar M. Osteoporosis in Older Adults. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Sep;104(5):873-884. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.06.004. Epub 2020 Jul 15. PMID: 32773051.

- Einhorn, T., Gerstenfeld, L. Fracture healing: mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11, 45–54 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2014.164

- Hao, B., Feng, H., Zhao, Z., Ye, Y., Wan, D., & Peng, G. (2020). Different types of bone fractures in dinosaur fossils. Historical Biology, 33, 1636 - 1641. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2020.1722661.

- Jordane Saunier, Roland Chapurlat, Stress fracture in athletes, Joint Bone Spine, Volume 85, Issue 3, 2018, Pages 307-310, ISSN 1297-319X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.04.013.

- Garner MR, Sethuraman SA, Schade MA, Boateng H. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Open Fractures: Evidence, Evolving Issues, and Recommendations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020 Apr 15;28(8):309-315. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00193. PMID: 31851021.

- Hussain MH, Ghaffar A, Choudry Q, Iqbal Z, Khan MN. Management of Fifth Metacarpal Neck Fracture (Boxer's Fracture): A Literature Review. Cureus. 2020 Jul 28;12(7):e9442. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9442. PMID: 32864266; PMCID: PMC7451089.

- Ho, H., Chen, C., Li, M., Hsu, Y., Kang, S., Liu, E., & Lee, K. (2014). A novel and effective acupuncture modality as a complementary therapy to acute pain relief in inpatients with rib fractures. Biomedical Journal, 37, 147 - 155. https://doi.org/10.4103/2319-4170.117895.

- Wicklein S, Gosch M. Osteoporose und Multimorbidität [Osteoporosis and multimorbidity]. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2019 Aug;52(5):433-439. German. doi: 10.1007/s00391-019-01569-5. Epub 2019 Jun 18. PMID: 31214779.

- John T. Schousboe, Suzanne N. Morin, Gregory A. Kline, Lisa M. Lix, William D. Leslie, Differential risk of fracture attributable to type 2 diabetes mellitus according to skeletal site, Bone, Volume 154, 2022, 116220, ISSN 8756-3282, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2021.116220.

- Carolina A. Moreira, John P. Bilezikian, Stress Fractures: Concepts and Therapeutics, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 102, Issue 2, 1 February 2017, Pages 525–534, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2720

- Yang, S., Ding, W., Feng, D., Gong, H., Zhu, D., Chen, B., & Chen, J. (2015). Loss of B cell regulatory function is associated with delayed healing in patients with tibia fracture. APMIS, 123, 975 - 985. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12439.

- Ghorbanhoseini, M., Riedel, M., Gonzalez, T., Hafezi, P., & Kwon, J. (2017). Is It "Fractured" or "Broken"? A Patient Survey Study to Assess Injury Comprehension after Orthopaedic Trauma.. The archives of bone and joint surgery, 5 4, 235-242 . https://doi.org/10.22038/ABJS.2017.19541.1507.

- O’Connell, B., Bosse, M. (2016). Fracture Immobilization and Splinting. In: Taylor, D., Sherry, S., Sing, R. (eds) Interventional Critical Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25286-5_37

- Espallargues, M., Sampietro-Colom, L., Estrada, M., Sola, M., Río, L., Setoain, J., & Granados, A. (2001). Identifying Bone-Mass-Related Risk Factors for Fracture to Guide Bone Densitometry Measurements: A Systematic Review of the Literature . Osteoporosis International, 12, 811-822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980170031.